5 Characteristics of Practical Karate

Shureimon, the “Shuri Gate” at Shurijo (Shuri Castle) on Okinawa

Karate is not a singular martial art, or training methodology, but rather an umbrella term for hundreds, if not thousands of different interrelated styles and training methodologies. This makes defining “karate” a challenge, and there is no universally accepted definition beyond the fact that the art is generally performed empty-handed, and originates from Okinawa or, more broadly, Japan. Unfortunately, this inconsistency in definition often makes it difficult to know what to expect from a given karate style or dojo. For this reason, many karateka have taken to adding labels to help clarify their approach to the art, and one such label which has been growing in popularity over the last few decades is “practical karate,” but what makes karate “practical?”

IMPACT TRAINING

Paul Musolf working hand conditioning on a stone while striking the makiwara to develop power generation

As the late Shorin-Ryu instructor, Richard Poage, liked to say, “if you want to be good at hitting things, you have to hit things.” While practical karate consists of many methods besides striking, the majority of karateka in the world have been introduced to karate as a primarily striking art. Even so, many karateka only practice their striking on empty air, and if you want your karate to be functional, pragmatic, and effective, you must incorporate actual impact into your training. There are many different types of impact training and training tools, all of which serve different functions in the process of improving your striking capabilities.

Higaonna Morio of Goju-Ryu demonstrating hand conditioning on a heavy stone

Hand conditioning is a popular example of impact training in karate because it can be flashy and impressive, both as a process and through demonstrations like tameshiwari (test breaking). Some notable Okinawan karate masters, such as Higaonna Morio of Goju-Ryu, and Shinjo Kiyohide of Uechi-Ryu, have often had their conditioning practices recorded and widely publicized, and it has been common on Okinawa to break boards and roofing tiles as part of demonstrations for as long as there have been karate demonstrations. These demonstrations have become incredibly popular, yet the vast majority of karateka will never engage in such intensive hand conditioning practices. Even so, all karateka can benefit from more moderate practices, as they take advantage of Wolff’s Law—a medical law which states that bones placed under stress will increase in density and strength—to help protect your hands from injury while striking.

Iron palm bag striking examples

Though not technically impact training, the easiest introduction to hand conditioning is simply performing push-ups on your striking knuckles, which helps strengthen not only the bones of the hand, but the joints, arms, and chest. While any impact training will have the side-effect of conditioning the striking surfaces you use, we should also consider training methods which are specifically intended for conditioning. When looking at such methods, we tend to see a fairly consistent theme: you strike an object, which has enough give to avoid injury, and you begin by striking weakly and progressively increase the power of your strikes over time, until you can strike a more solid object and start the process over. A good modern option for this is a yoga block, which is made from dense foam that is made to support body weight without collapsing, but which still has some give to it. A more traditional, homemade solution is a bag filled with rice, mung beans, or sand, which can be wrapped with duct tape to make it firm. There are also several manufacturers that make purpose built “iron palm bags” for this type of training. For most karateka, consistently striking such objects will provide plenty of conditioning for their needs, though some may work their way up to striking bags filled with lead or steel shot, or even stones. It is important to know that increasing your striking power, or the density of your target, too quickly can result in lasting injury, so it is vital that you listen to your body, and you should, of course, seek a knowledgeable instructor to help you through the process.

Noah Legel and Richard Poage performing the “three stars hitting” kote kitae exercise

In addition to conditioning the hands, it is common practice in karate to condition other parts of the body through tai tanren (lit. “body conditioning”) exercises. Some of these exercises are performed with partners, while others are performed with equipment, in much the same manner as you would with conditioning your hands. The most popular of these being kote kitae (lit. “forearm forging”) exercises where you clash your forearms with a partner’s forearms in various patterns, usually through movements like your basic uke-waza (lit. “receiving techniques), such as in the “three stars hitting” exercise that is found almost universally across Chinese and Okinawan martial arts. Additionally, you will find schools that throw kicks to the legs, and kicks or punches to the body, in order to toughen those areas, as well. This is beneficial practice, both for hitting, and for being hit, which is bound to occur during violent altercations.

Uechi-Ryu master, Gushi Shinyu, working with a taketaba

When you don’t have a partner available, it’s good to have tools available to continue your body conditioning by yourself. One such tool is the taketaba (lit. “bamboo bundle”), which can be oriented either horizontally or vertically, and can be struck with a wide variety of techniques in order to toughen them. Sometimes, these are even used by thrusting the fingers into the bundle to toughen them for striking. There are also small, handheld versions of this tool, along with modern metal versions called tetsutaba (lit. “iron bundle”), which can be used to hit your body all over for conditioning. When bamboo is not available, some people build what are called “ude-makiwara” (lit. “arm wrapped rope”), which are round wooden posts that have been split several times down the middle and wrapped with rope or other padding in order to give it some give. It is important that such tools are not solid and immovable, otherwise you are much more likely to injure yourself.

Bruce Lee working with a heavy bag

Perhaps the most well-known and consistently present form of impact training in martial arts is striking some form of hanging bag, whether it is a massive 300lbs+ heavy bag or a nearly weightless double-end bag, and each has its benefits. In karate’s past, cloth bags filled with sand, called sunabukuro (lit. “sand bag”), were used both for conditioning, as described above, and for striking training similar to what is done with modern heavy bags. While such tools can absolutely still be used, there is no reason for us to avoid using modern tools. The Okinawan masters of the past would doubtless have used many of the tools we now have available if they had been able to.

A typical boxing-style punching bag

Heavy bags are especially useful for working full-power, full-speed striking combinations on a target that feels similar to striking the body of an opponent, and can be used to provide feedback on the quality if your strikes, as the bag will bounce when struck properly, but swing when pushed by a strike. These bags vary widely in size, style, and weight, but are usually 4ft-6ft in height, cylindrical, and at least 50lbs. Some bags are specially designed for specific types of training, such as “wrecking ball” bags, which are spherical and allow for upward and downward strikes. There are also several materials you might find used to fill the bags, from scraps of fabric, to foam, to water, and some have sand bags added to them to increase their weight, although those tend to shift to the bottom over time, resulting in a very hard striking surface in that area. While hitting a heavy bag consistently over time will naturally result in an increase in bone density, it is easy to go too hard, too soon, if this occurs, as the bag moves around and you may end up landing a strike where you did not intend, so it is important to be cautious enough to avoid injury when using such heavy bags.

A typical boxing-style double-end bag

Double-end bags are small, light bags which are both hung from overhead and weighted or anchored to the ground, typically by elastic or rubber attachments. This allows the bag to bounce and move erratically when struck, which it does more quickly the harder it is struck. Unlike a heavy bag, this is less about feedback and power development and more about speed, reaction time, accuracy, and rhythm. People rarely stand still when you hit them, so it is very beneficial to learn how to strike a moving target. The double-end bag can also be used to emulate counterattacks, which must be evaded or blocked. There are also freestanding bags which hold a similar bag up on a spring-loaded arm, which function very much the same way, but can be easily moved around a training area, unlike a typical double-end bag, which requires an overhead anchor point, and sometimes a floor anchor, if they do not come with a weighted base.

Noah Legel holding Thai pads for Stephanie Legel

Focus mitts, Thai pads, and kicking shields all have benefits that bags do not, and that is the ability to move with a person, and present specific targets to emulate striking combinations. While heavy bags and double-end bags can bounce and swing, they are isolated to one area of the floor, and they are not shaped like people, meaning you have to imagine your targets on a surface that may be the wrong shape, angle, or position. When a person is holding pads, they can move anywhere, and hold them at very specific angles and positions, allowing for a wide variety of strikes to be thrown to targets that better emulate a real human target. Another benefit is that the padholder can provide immediate feedback on your techniques, and can throw strikes back at you for you to respond to, either by evading the strikes or blocking them, which better emulates a fight than an inanimate bag.

A typical modern makiwara, with rope added around the padded striking area

Perhaps the most misunderstood impact training tool in karate is the makiwara (lit. “wrapped rope”), sometimes referred to as a “striking post.” The name actually comes from the large bundles of rice rope used as training targets in Japanese archery, which were downsized and tied to the top of a flexible board to act as padding before the modern foam and leather pads that can be purchased, nowadays. Some people still prefer the rope pads, both because they help toughen the skin of the hands and because the added texture allows you to strike from various angles without sliding off the pad, as can happen with the smooth leather pads. Because of the callouses this tool can build on the knuckles, and potential misinterpretations and mistranslations of guidance from Okinawan instructors, many people mistakenly believe that this tool is meant for hand conditioning. In reality, the makiwara is an incredible tool for learning and developing structure and power generation, thanks to how they are made.

Modern examples of false makiwara

Often, you will see people using “makiwara” that are improperly made, which tends to eliminate all of the benefits that you are supposed to get from the tool. The most popular examples are wall-mounted “clapper” makiwara, or simple padding on solid boards. Even makiwara that appear to be built traditionally can be deceiving, because they may not flex in the manner a makiwara. This can be anything from using a wood that doesn’t bend, boards that are too thick, or even simply tying a pad to a tree. Using tools like this will toughen the hands, but are much more likely to cause health issues over time than a properly build makiwara, and the conditioning is really the only benefit you gain from using them. In an attempt to build makiwara that can be moved around, or are non-permanent, some people try setting them into buckets of concrete, but this is not sufficient to anchor the tool in place, so even if the makiwara is otherwise built properly, it will not function as intended.

Ryan Parker’s indoor makiwara built on a platform using a leaf spring design

A real makiwara is meant to act like a spring, absorbing the force of your strikes and returning it to you in kind. This can be done by cutting a board at an angle so that it tapers, making thinner on top than at the bottom, or by layering multiple boards of progressively shorter lengths against each other, much the same way that modern automobile leaf springs are made. These are typically mounted in the ground, like a fence post, but can also be anchored to walls, the floor, or even wooden platforms that can be moved around. The important thing is that the tool flexes when struck, and pushes back as hard as you hit it. This is what creates the immediate feedback that will highlight flaws in your structure, as well as weak muscles in the kinetic chain of your strikes, and the resistance it provides will actually help strengthen that kinetic chain the more you use it. If your wrist isn’t properly aligned, it will buckle. If your lats aren’t engaged, your elbow will flare out and your shoulder will hunch up. If your core isn’t engaged, you will be forced to lean back. If your stance isn’t stable, you will be rocked back on your heels. There is no other single impact training tool that can provide all of the benefits that the makiwara provides.

GRAPPLING

Noah Legel applying juji-gatame (lit. “cross hold”) during sparring

Karate relies very heavily on fighting methods which touch, grab, push and pull the opponent (generally referred to as tuidi-waza (lit. “seizing hand techniques”), along with joint locks, strangle holds, and takedowns), making it a grappling art as much as it is a striking art. Since the art was developed for self-defense, law enforcement, and security work, the majority of this grappling is done from a standing position, but it is important to be familiar with all ranges of violence, including groundwork. Too many karateka ignore grappling, entirely, which has left them unaware of how to apply the majority of their kata techniques, at all, and even those who do practice grappling techniques often do not engage in enough fundamental grappling training to be able to use those techniques under pressure. Often, instructors who are unfamiliar with grappling fundamentals will rely on what they call “anti-grappling” techniques, but in reality, the only “anti-grappling” that exists is grappling.

Two Okinawans engaged in tegumi

Historically, the majority of young men on Okinawa practiced a folkstyle submission grappling sport called “tegumi” (lit. “hand crossing"), or “muto” (lit. “no-sword”), where takedowns, joint locks, strangle holds, and pins were allowed. This means that the karate masters of old likely had this background, making them familiar with general grappling skills and techniques. In the modern day, this sport is largely extinct, having been converted into a Sumo-inspired sport called Okinawan shima, which no longer utilizes submissions or pins. We also know that many of those masters engaged in cross-training, either as pastimes or as part of their careers, including arts such as Japanese koryu jujutsu, Sumo, Judo, and Aikido. This tradition of cross-training has fallen out of favor in most karate dojo, but is a very beneficial practice. If you do not engage in such cross-training, it becomes even more important for you to incorporate fundamental grappling into your regular karate training.

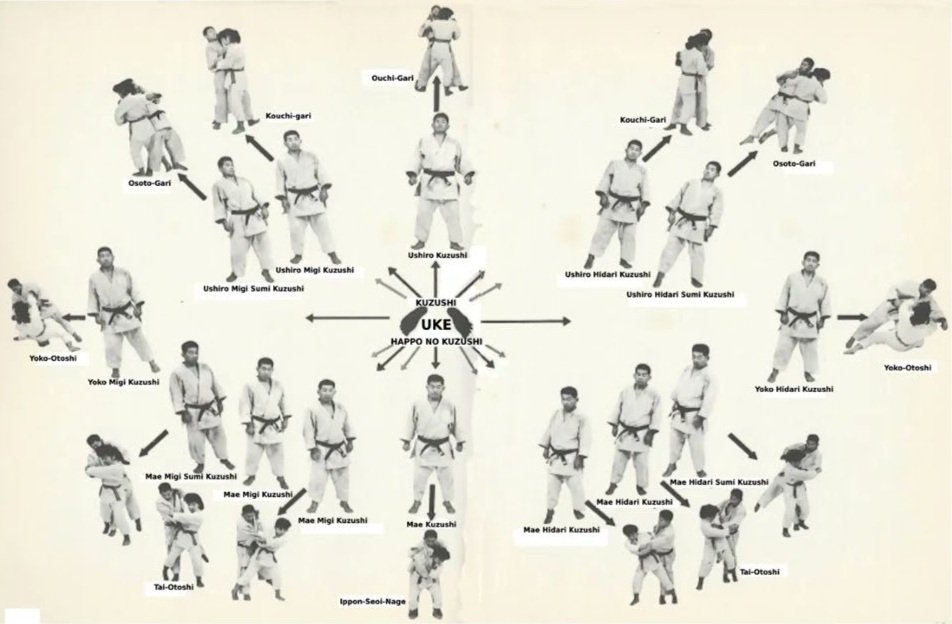

A happo no kuzushi chart for Judo

When looking at standing grappling, perhaps the most important thing you need to learn is kuzushi (lit. “off-balancing”), as it can be almost impossible to throw an opponent to the ground without it, and it can also make it easy to apply other grappling techniques, and even strikes. Kuzushi is typically expressed through charts called “happo no kuzushi” (lit. “eight directions of off-balancing”), which shows how a person can be moved forward, backward, sideways, and to the angles, in order to force them off-balance so you can apply throws and other techniques. This is a good visualization tool, and many drills can be used to practice it, including uchikomi (lit. “entry practice”).

Two wrestlers engaging in chest pummeling, trying to get to a body lock

In addition to kuzushi, there are a collection of positions within grappling that are vital to know in order to be able to access certain techniques. When grappling from a standing position, these include the double collar tie, single collar tie, overhook, underhook, over-under, body lock, bicep control, and wrist control. These positions are often worked through various drills called “pummeling,” where two partners alternate between the positions, typically with the intent of getting to the strongest position possible. Those drills work very well as platform drills, where you can jump into techniques in the middle of the drill. This, in conjunction with kuzushi drills, make for an excellent way to teach students how to find openings for grappling techniques.

A Judoka passing the guard of another Judoka

On the ground, there are fewer fundamental positions to consider, but they are just as important. These would be full mount, half mount, side mount, north-south mount, back mount, full guard, and half guard. In addition, there are foundational movements that are critical to being able to maneuver on the ground: bridging and shrimping. In grappling arts, it is common to use those movements to move between the various positions, and this can act as a platform for ground-based fighting techniques in much the same way that pummeling does for standing techniques. Given the intent of karate, it is especially important to work on getting back to a standing position, rather than simply trying to beat someone at grappling. This is typically done through a technique called the “technical” or “tactical standup,” but if you do not understand how to grapple on the ground, you may find yourself unable to use that technique and get back to your feet.

KATA APPLICATIONS

To’on-Ryu founder, Kyoda Jutatsu, and Goju-Ryu founder, Miyagi Chojun, demonstrating a takedown from kata

Karate without kata (lit. “forms”) is generally considered to not actually be karate, anymore, as they are the core of karate curriculum. Unfortunately, while the modern tradition of karate has maintained this belief, it typically does so without actually using the kata for their intended purpose, resulting in the kata losing their value, and no longer being core to karate. If you are going to practice kata, it stands to reason that they should serve a purpose, and that purpose should be more than simply being exercise or “moving meditation.” The kata were designed to record combative templates for Okinawan nobility to use for self-defense, or for their duties as police and bodyguards, and include limb control methods, strikes, joint locks, strangle holds, and takedowns for those contexts. Originally, the fighting techniques would have been taught prior to learning the solo kata, but over time that has changed, especially as practical application has been removed. These days, it is incredibly rare to find a style of karate which has preserved all of the intended applications of their kata, and so we largely do not know what the original applications were. Even so, we do have many examples, as well as documentation on how to interpret kata, and we know the contexts for which the art was developed. Combined with knowledge of common acts of violence, this allows us to perform bunkai (lit. “break apart and analyze”) in order to extract oyo (lit. “practical applications”) and henka (lit. “variations”) from the solo kata. This restores the value of kata, including the value of its solo performance, which can reinforce and accelerate the learning process once the student has applications they can visualize during their physical performance.

Leigh Simms demonstrating one basic example of the application of hikite from kata

From the examples we have available, we can extrapolate many more potential kata applications. One such example is tied to a concept called meotode (lit. “husband and wife hands”), where both hands are used, together, such that one hand supports the action of the other. This is seen most clearly in the hikite (pulling hand) that is found, in some for or another, in every karate kata. The name gives away its purpose—to pull something—and not only have past masters, such as Funakoshi Gichin (founder of Shotokan), written that its function is to pull part of the opponent, but we also have existing examples of it being used as such in various styles. Despite this, there are many who still believe that the function of hikite is to generate power, which has been debunked on numerous occasions. It is important to understand and embrace hikite, and other examples of meotode, such as pinning the opponent’s arm to your chest while striking to the neck, as in shuto-uke/tiigatana (lit. “sword hand receiver”/”hand sword”), or pulling the opponent’s arm down as you strike over the top, as in yama-zuki (lit. “mountain thrust”), or the backfist seen in Naihanchi. Simply remembering and utilizing this fundamental concept will unlock much of what the kata have to offer.

Shindo Jinen-Ryu founder, Konishi Yasuhiro, and Motobu Kenpo founder, Motobu Choki, demonstrating Naihanchi applications

Examples of specific kata applications can be found from many sources, but they are not always labeled as such, which can make it difficult for those new to the study of kata to find them. Additionally, many sources are only available in Japanese, which is limiting for anyone who cannot read the language. For example, these photographs were not next to each other in the book they were published in, which was written in Japanese. When they are put side-by-side, it is easy to see that the partnered techniques fit the kata postures shown, but this takes an awareness and understanding of how kata movements and postures can be applied. To that end, we can refer to various guidelines for analyzing kata.

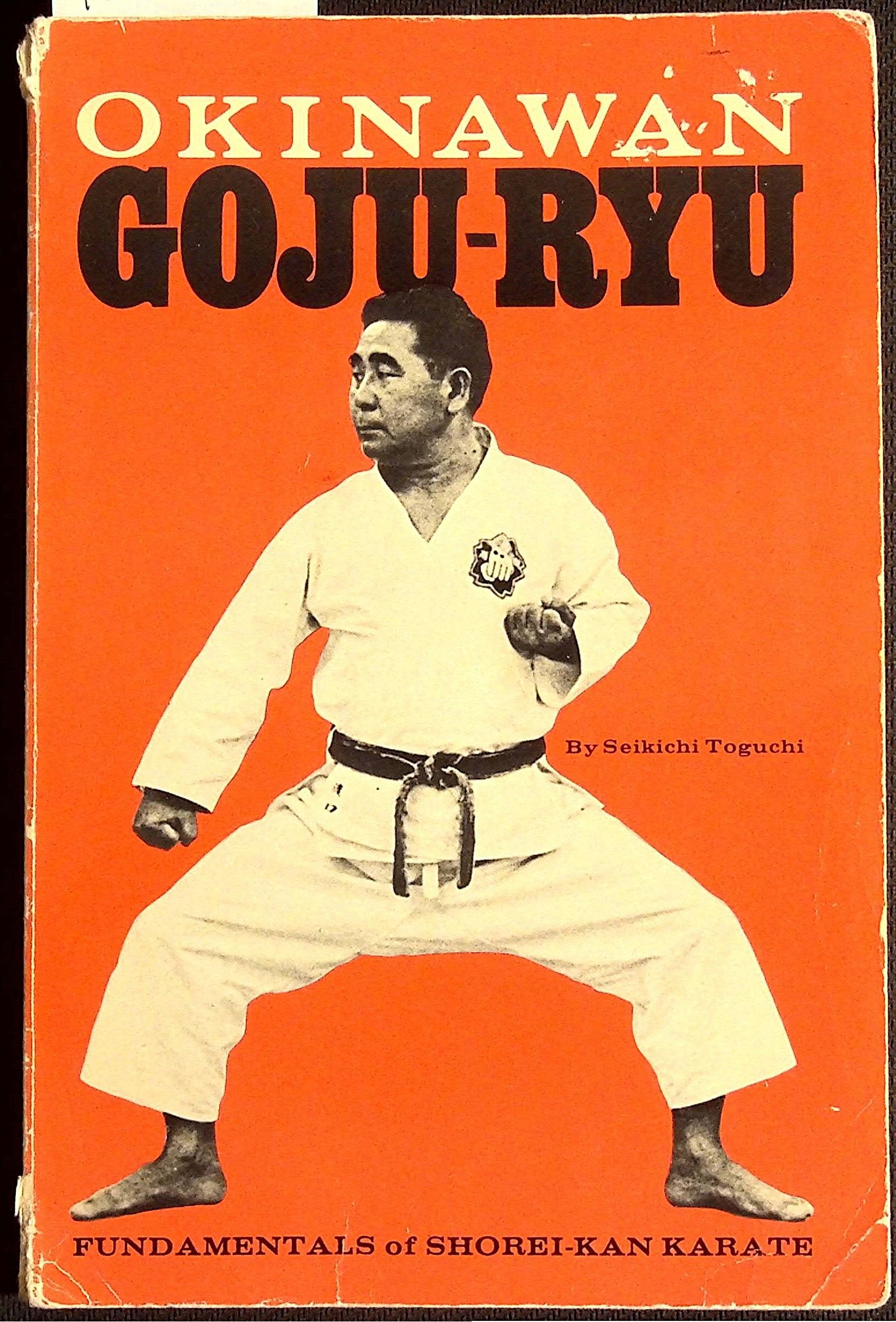

Toguchi Seikichi’s first book on Goju-Ryu in a series where he includes kaisai no genri

The late Goju-Ryu master, Toguchi Seikichi, who trained in Te/Ti with his father, then Goju-Ryu with Higa Seko and Miyagi Chojun (the founder of Goju-Ryu), is particularly notable for having published a set of guidelines for understanding the koryu (lit. “old style”) kata of karate, which he supposedly received from Miyagi Chojun. These guidelines are collectively known as “kaisai no genri” (lit. “understanding and judging of fundamental truth”), and while they do not necessarily apply universally across all kata and styles, they are an excellent starting point. These and other details on kata bunkai can be found in Noah Legel’s article, “How to Bunkai.” Other great resources for those just starting out with practical kata application are the books “The Way of Kata,” by Lawrence Kane and Kris Wilder, and “Bunkai Jutsu,” by Iain Abernethy.

A screenshot from CCTV footage of a woman being assaulted by a man while using an access keypad

As you go through the process of bunkai, you must keep the contexts of karate in mind; self-defense, law enforcement, and security/bodyguard work. These all occur at close range, which means that the applications you find for the kata will largely be close range techniques, and are most likely intended to be used against untrained people, who may or may not be experienced with violence. The big difference between self-defense and the other two contexts are that the focus of self-defense is on getting home safely, while law enforcement and security/bodyguard work will generally have a focus on restraining an attacker so they can be arrested, which means you may have to engage with the attacker for far longer than you might in self-defense. In all cases, it is important to be familiar with statistically-likely attacks, as you should be testing your kata applications against those attacks. There is nothing wrong with incorporating trained attacks into your training, especially if you plan to compete in some form of combat sports, but if your intent is to prepare yourself for self-defense situations, or for law enforcement and security/bodyguard work, it is more efficient to focus on the methods untrained people will commonly use to attack you. There are lists of such attacks available from various martial artists and law enforcement agencies, and you can also do your own research by looking up CCTV and cell phone footage of real assaults to see what real attacks look like. These attacks will also tend to vary based on the victim and assailant; for example, a man will tend to attack a woman differently than he attacks another man, or how he attacks a child. Some law enforcement agencies also follow the “+1 Factor” theory in their training, where it should be expected that after a certain amount of time (typically between 10-30 seconds), some additional factor will be introduced to a fight, such as a second attacker or a weapon.

SELF-DEFENSE SKILLS

The only known image of Itosu Anko, the master who introduced karate to the Okinawan school system

There is far more to self-defense than fighting skills, and this is far too often neglected in karate schools, even when they claim to teach self-defense. This goes beyond the techniques you train and gets into how you train, as well as how you live your day-to-day life. Part of this goes back to the contexts of karate, in that you must understand the difference between consensual violence and non-consensual violence, as karate was intended to deal with non-consensual violence, which was even explicitly stated by famous karate master, Itosu Anko, in his very first of 10 Precepts: “Karate is not merely practiced for your own benefit; it can be used to protect one's family or master. It is not intended to be used against a single adversary but instead as a way of avoiding injury by using the hands and feet should one by any chance be confronted by a villain or ruffian.” Motobu Choki also spoke to this, when he said: “The techniques of kata have their limits and were never intended to be used against an opponent in an arena or on a battlefield.” We know that the methods of kata were designed for dealing with untrained attackers in non-consensual violence, as opposed to trained opponents in consensual violence.

Col. Jeff Cooper’s Color Codes of Awareness, which were originally used to describe combat readiness, but which can also be applied to self-defense

The best self-defense is to avoid such situations altogether. This is fairly easy to do with consensual violence, as you can almost always choose to lose face and forfeit before a fight starts. Unfortunately, this can be difficult for some people—particularly young men who have been socially conditioned to feel their masculinity is tied to their ability to beat other men in a fight. For this reason, it is important to emphasize to students how dangerous “street fights” can be—people can, and do, die as a result of such encounters, and consensual street fights are also illegal in all but 2 States in the USA. It is also important to discuss methods for remaining calm under pressure, which is best done through role-playing scenarios that might lead up to a fight, as well as physical pressure testing methods, which will be discussed later. These role-playing scenarios can also be used to practice escaping from or preventing non-consensual violence. These practices can be awkward and uncomfortable, particularly for those who don’t have a background in theatre/drama, but if you claim to teach self-defense, they must be part of your curriculum. Introduce situations where students may have to identify threats in a group, or find ways to escape before an attacker can do anything to them, or even talk someone down using de-escalation techniques in order to stop a fight before it starts. Good daily practices for maintaining situational awareness should also be discussed, such as staying away from the wall when walking past corners, checking under your vehicle and in your back seat before getting in, maintaining distance from strangers, staying off your phone and not wearing headphones in public, covering your drink at all times, and more. You must also understand the “Risky Four” (formerly called the “Four Stupids,” but that name inherently blames the victim, which is unhelpful), which are “risky places,” “risky things/activities,” “risky times,” and “risky people.” It is up to you to determine how much risk you are willing to accept in life, and no one is saying that you should become a hermit in order to keep yourself safe, but understanding the types of situations that put you at greater risk than normal is important to making informed decisions.

PRESSURE TESTING

Noah Legel demonstrating a tuidi application for the chuge-uke (middle/low receiver) posture of Naihanchi

It is one thing to memorize drills and kata applications, but it is quite another to actually put your ability to perform those under pressure to the test. There is a belief among some karateka that simply performing the solo kata will eventually lead to understanding and the ability to apply them, but this is simply untrue. Still others have a tendency to “collect” drills and applications, without ever internalizing them, and believe that this will prepare them for real self-defense situations. The fact of the matter is that, unless you’ve performed a particular technique under pressure that emulates the stress you will be under in a real situation, you are highly unlikely to be able to perform it in a real situation. In the words of Iain Abernethy: “If you haven’t done it live, you haven’t done it.” The trouble then becomes; how do you pressure test yourself and your material? Most karateka only engage in one form of pressure testing, and that is whatever form of kumite their dojo, organization, or style tends to participate in, which is almost always based on one of three competition karate formats: point fighting, kickboxing, and knockdown fighting. Unfortunately, while each has value, none of those is particularly ideal for testing the classical methods of karate.

Kendoka competing to land the first strike to earn a point

Point fighting is a direct transplant of Kendo competition rules, which is why it focuses so heavily on long range methods and scoring based on landing a single strike first, as if you were fighting with a sword. It was in no way designed with karate in mind, and was instead meant to allow for ease of popularizing the ruleset within the Japanese university system. American kickboxing is a further evolution of point fighting, primarily pioneered by point karate competitors who wanted something full-contact and continuous to compete in, so they blended what they knew with Western boxing. Knockdown fighting, on the other hand, was primarily an evolution of the irikumi-go (lit. “hard inside grappling”) that Kyokushin founder, Oyama Masutatsu, learned from his Goju-Kai experience. It is difficult to say how much influence he took from his Shotokan experience in the development of his sparring format, but the distinct lack of grappling means that it is still of limited value for testing the methods of kata. Modern offshoots, such as Kudo, have blended Kyokushin with Judo to bring grappling back into the art, but the stylistic expression of fighting still looks more like Kyokushin and Judo mixed together than a holistic fighting system designed for self-defense, law enforcement, and security/bodyguard work. All of these methods can be enjoyable practices, and can teach skills which have crossover into those contexts, but should not be the only type of pressure testing that practically-minded karateka engage in. A layered approach is much more thorough and well-rounded.

Kickboxers fighting in a competitive match, which is a symmetrical pressure testing method

There are two categories of pressure testing methods: symmetrical and asymmetrical. The competition sparring formats previously mentioned are all symmetrical pressure testing methods, as both participants are using the same skill sets and following the same set of rules. This is beneficial for learning how to handle trained responses, and testing overall skill against other people in order to compare yourself to a baseline. Asymmetrical methods, on the other hand, feature different skill sets and rules for the participants, depending on the goals of a given training session. This allows for training that is custom tailored to developing skill for self-defense, which is inherently asymmetrical in nature, and for isolating specific skill sets that need to be improved. Both approaches have their place in practical karate training.

Samir Berardo explaining kakedameshi practice at a seminar in Brazil

Perhaps the most appropriate, and yet least practiced symmetrical sparring method for classical karate is kakedameshi (lit. “test of crossed/hanging hands”). This practice is often mistakenly believed to be “street fights,” but was actually method of challenging other karateka by sparring while maintaining contact at all times, which Matsubayashi-Ryu founder, Nagamine Shoshin, described as being like a very aggressive form of Chinese push hands, but which includes strikes, locks, takedowns, etc. A more accurate interpretation, therefore, is that it is “sticky hands” sparring. Participants cross their arms at the wrist (either one arm each, or both arms), and attempt to use the applications of their kata to fight, all while maintaining at least one point of contact with their opponent the entire time. This is excellent for developing tactile sensitivity (the ability to maintain contact with an opponent and know where they are in space and how they are moving), which lends itself to a wide array of grappling methods. The fact that it forces participants to remain at close range also means that you have access to almost all of your kata applications, as they were largely designed for that range of combat. Of course, this is not a perfect emulation of real-world violence, as a real attacker is not going to try to maintain contact with you, and will not be trained in the same types of techniques, so it is not sufficient, by itself, to prepare you for self-defense situations.

Noah Legel winning an MMA fight against a state champion wrestler with a head kick

The next best option for symmetrical pressure testing your karate is actually MMA (mixed martial arts) sparring, which may surprise many. This approach is the most open ruleset in the modern era of martial arts, allowing for long range, middle range, close range, and ground fighting techniques, including both striking and grappling methods. While self-defense does, by-and-large, happen at close range, it is beneficial to be comfortable fighting at long and middle range, particularly when multiple opponents are involved, as evasive movement becomes vital to your ability to maintain distance, stack the opponents so you don’t have to fight them all at once, and finding openings to escape. This method also has the benefit of exposing you to a wide array of attacks, and while they will be trained attacks, there is crossover between them and untrained attacks, and it provides you an opportunity to test all of your skills against someone who understands how to counter them. Even this, however, is insufficient for preparing you for self-defense, as it lacks the full context of those situations, and doesn’t look the same, so you need to incorporate resistance training methods that are tailor-made for self-defense.

Two of Noah Legel’s students engaged in “bully sparring”

The most common form of asymmetrical sparring that martial artists tend to be familiar with are style vs. style pairings, which are excellent for focusing your training to develop desired skills. For example, assigning one participant as a boxer, only allowed to punch, while the other is a kicker, or one person is only allowed to strike while the other is only allowed to grapple. This can be done either to force a participant to use a skill set they need more practice with, or to defend against a skill set they need to learn more about. This approach can be used to acclimate participants to self-defense by setting parameters that establish one person as a defender, and one as an attacker, such as the practice that I refer to as “bully sparring.” This is where the attacker’s job is to keep punching, no matter what, until the defender does something to make them stop, while the defender’s job is to stop the attacker as quickly as possible. Of course, there is an aspect of role playing to this, as it is unsafe to use certain highly effective techniques at full power, such as elbows and knees to the face, or strikes to the eyes, throat, or groin. The attacker has to be aware of these techniques, and make a judgement call during the session as to when the defender has done enough to stop them. This can be expanded such that the attacker can use any number of common acts of violence in order to expose the defender to a wide array of attacks that they might encounter in self-defense. One of the major benefits of the bully sparring approach is that it puts the defender in a situation where the attacker doesn’t stop just because they did a technique, and really puts the defender under a lot of intense pressure in a very short amount of time as the attacker tries to overwhelm them.

Participants in a “simulation day” exercise as part of John Titchen’s DART (Defense Attack Resolution Tactics) program simulating a reality-based self-defense scenario

The epitome of asymmetrical pressure testing, as it relates to the intended contexts of karate, is the practice of self-defense scenario exercises, but these are perhaps the most neglected sparring practice in all of martial arts. This is because most people are uncomfortable with the idea of acting, or role playing, and most instructors do not take the time to analyze real-world self-defense situations in order to formulate such exercises. The latter is easily remedied by research, but the former can only be addressed by getting students accustomed to the practice over time. This can start with something as simple as a kata application drill that begins with the attacker yelling at the defender before attacking with a known attack, and evolve over time to full scenes, including bystanders, multiple attackers, or weapons, and which can be resolved by de-escalation, escape, or threat elimination. As with bully sparring, the attacker(s) must be aware of what the defender is doing and respond appropriately, up to and including acting as if they were knocked out. Hard contact to the body and limbs is largely fine, but head contact must be controlled to avoid brain injury, and contact to vulnerable targets like the eyes, throat, and groin must either be adjusted to safer, nearby targets, or done with control so as to not injure anyone.

CONCLUSION

There are many different expressions of karate, even within the practical karate community, but when effectiveness is the measure of your training, rather than aesthetics or adherence to tradition, it is important to incorporate certain methodologies into your training. While there can be many more, there are at least five key characteristics of effective practical karate training:

Impact Training

Grappling

Kata Application

Self-Defense Skills

Pressure Testing

When all of these methodologies are combined, you will have a well-rounded martial arts experience that can prepare you for real-world self-defense situations. In the end, the individual practitioner is responsible for the intensity and consistency of their training, which is the final deciding factor in whether or not they are as prepared as possible, but it is up to the instructor to provide the opportunities the student needs.